The links between research and teaching

10 August 2017 | news

A defining characteristic of New Zealand universities is the statutory requirement that requires degrees to be taught mainly by people engaged in research.

This discussion asks how and why teaching and research are linked and compares New Zealand with the situation internationally. It considers what impact research has on teaching and how universities ensure their dual focus on research and teaching quality.

The graduate profile of a university qualification in NZ and the link to research

Every qualification offered by a New Zealand university is based on a graduate profile that clearly defines what skills and capabilities a graduate is expected to acquire if they successfully complete their studies. The majority of graduate profiles are now developed with sign-off from professional bodies (where they exist) and/or input from employers.

All degree-level qualifications are gained by successfully completing a structured 3-4-year curriculum, with periodic assessments that ensure students finish their studies with the skills and capabilities detailed in the graduate profile.

Lower-level (sub-degree) qualifications typically focus on the skills and capabilities a completing student will need to carry out a job or tasks where there are standard solutions and approaches. By contrast, a degree-level qualification will focus on developing the skills and capabilities that allow graduates to deal with work (and life) challenges that are complex and often lack a standard solution.

The graduate profiles for higher level qualifications therefore commonly include all of the following skills and capabilities;

- Discipline-specific expertise - Understanding current practice or knowledge and the major concepts and theoretical models relevant to their field.

- Critical thinking and reasoning - Being able to search the existing body of knowledge and to evaluate and critique what they find.

- Problem-solving - Developing new and innovative solutions to problems after applying appropriate judgement and analysis.

- Communicating - Communicating complex ideas well in person and in writing.

- Analytical skills – being able to apply quantitative and qualitative analysis to problems.

- Teamwork - Working well in teams.

- Time management

- Self-directed learning and development.

To varying extents, all of these skills and capabilities are also used in research. Therefore, research-led teaching models (see definitions below) are seen as being particularly effective ways of developing these skills and capabilities.

Universities believe that these skills and capabilities are best developed through teachers who also have expertise in them. Therefore, universities require academics who are teaching, particularly at higher levels, to be active and capable researchers.

In saying this, universities do not believe that being a good researcher will automatically make an academic a good teacher. Universities know that teaching is a skill that requires development and that, even with training and support, not every researcher can become a competent teacher. However, universities also believe that an academic cannot be a good teacher of higher-level degrees unless they are also a competent researcher.

The link between teaching and research

There is no single view as to how teaching and research should be linked but most tertiary education does link them through the following spectrum of approaches;

| Teaching Model | Research skills and experience required of the teacher | |

| Research- Informed Teaching | Research-informed – where curriculum reflects latest thinking and knowledge in the field of study. |

Minimal – they can deliver curriculum designed by someone else or are teaching an applied programme that will not require many of the higher-level capabilities and skills.

|

| Research -Led Teaching | Research-driven – where students are taught research findings in their field of study; |

Intermediate – they need relatively good understanding of the body of research and knowledge in their field |

| Research-oriented – where students learn research processes and methodologies. |

Intermediate – they need at least basic research skills in locating and evaluating primary and secondary sources and in presenting analysis and thinking. |

|

| Research-tutored – where students learn through critique and wide-ranging discussion between themselves and staff who can draw upon a deep understanding of thinking and knowledge in their field. |

Advanced – they need a deep and current knowledge of their field. (See case study below) |

|

| Research-based learning – where students learn as researchers and develop research skills on actual projects led by academic staff. |

Advanced – they need to be active researchers. |

All five models operate widely within every New Zealand university and most individual university courses will draw on more than one of them.

By the second or third year of an undergraduate university degree and for all post-graduate university qualifications, most or all teaching will be research-led.

Case-Study – Research-tutored learning

Ask someone who attended a university more than a decade ago what teaching looks like at a university and they will probably talk about sitting in a tiered lecture theatre receiving information from a lecturer.

Ask someone at university now the same question and you are just as likely to be told about learning in ways that require active participation and engagement by the student. The tiered lecture theatres of the past are progressively being replaced with large flat-floor rooms with moveable tables and chairs. Students may be given a problem and asked to break into groups to discuss how to approach it – in ways that simulate how they would approach similar real-world problems in a work place. They will then discuss their approaches and ideas with the wider group.

This approach needs teachers who are able to handle flexible, wide-ranging discussions with their students. These are usually people who are research-active and expert in their fields – hence the commitment to research-tutored teaching.

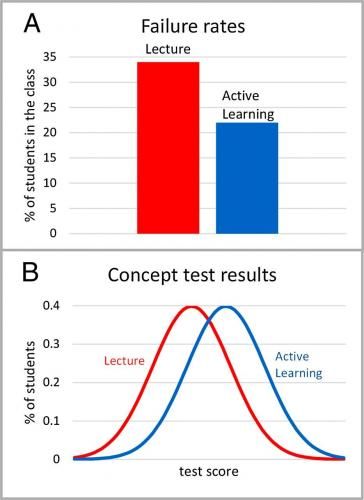

Stanford University’s Professor Carl Weiman has evaluated the use of active participation methodologies in teaching large mathematics and science courses[1]. As shown in the two illustrations, failure rates (Illustration A) are lower when students are in an active learning environment versus a lecture environment and test scores are higher (Illustration B).

As a consequence of this work, more than half of Stanford’s teaching has now moved to being delivered via active learning from research-active teachers.

All New Zealand universities are well advanced in adopting the same approach to teaching.

[1] Wieman, C. (A) Failure rates for the active learning courses and the lecture courses. (B) Shift in distribution of student scores on concept inventory tests. Comparisons of average results for studies reported in Freeman S, et al. (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:8410–8415.

How normal is it for universities to focus on both teaching and research internationally?

Every university, teaching at post-graduate level and ranked in the top 500 by either QS or Times Higher, follows the research-led model of teaching.

There are a range of institutions internationally that call themselves universities but are actually polytechnics, institutes of technology, or American-style community colleges offering two-year undergraduate diplomas. These are more likely to be research-informed, rather than research-led.

Notwithstanding the above, New Zealand is unusual in having legislation that enshrines a link at degree level between research and teaching.

Are there trade-offs between teaching and research in New Zealand?

Every profession requires trade-offs and balancing of expectations; academia is no different. Academic staff of New Zealand universities are subject to (typically annual) performance appraisals that consider their competence and performance as both teachers and researchers and they cannot be promoted unless they are competent in both areas. Competency is assessed through a variety of means, including student evaluation, moderation, student grades and completion results, supervisory reports, and peer review.

New Zealand universities earn a quarter of their income from research and much of the rest comes from teaching. This puts a powerful incentive for universities to ensure teaching is of high quality and leads to good graduate outcomes. Notwithstanding this, international rankings which are important in the recruitment of academic staff and international students, are primarily driven by research citation rates and academic reputation.

As such, all New Zealand universities are focussed on ensuring academics deliver well on both their teaching and research requirements.

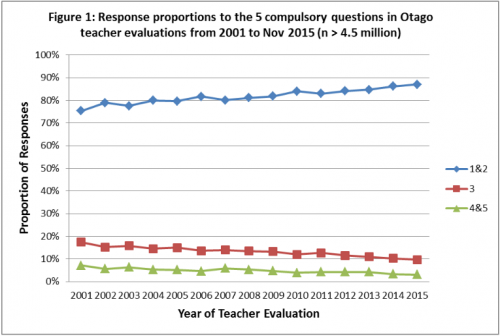

By way of one example, the table below shows the cumulative responses from all University of Otago course student evaluations between 2001 and 2015. A rating of 1 or 2 is a student satisfaction rate of excellent or good. A 4 or 5 is below average or very poor.

Source: University of Otago

It can be seen that student satisfaction with teaching increased continually over the period. Note that the Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF) was introduced in 2003. Thus, the claims that it has led to a decline in the emphasis on teaching and teaching quality are not supported by these data.

For more information:

- The Education Act 1989 S253B allows NZQA and NZVCC (via CUAP) to grant the awarding of a degree-level qualification (bachelors, masters or PhD) only where “it is taught mainly by people engaged in research”.

- S162(4) of the same Act requires includes the following characteristics of universities (a)(ii) “their research and teaching are closely interdependent and most of their teaching is done by people who are active in advancing knowledge”, and (a)(iii) “they meet international standards of research and teaching”.

- Contact Chris Whelan, Executive Director, Universities NZ.